The Problem with Clones in Rust - Why Functional Rust is Slower Than You Think (And How to Fix It)

Essay - Published: 2026.02.18 | 6 min read (1,562 words)

build | create | rust | software-engineering

DISCLOSURE: If you buy through affiliate links, I may earn a small commission. (disclosures)

I've been exploring High Level Rust as a way to get 80% of Rust's benefits with 20% of the pain. The core idea: use immutable data with functional pipelines and generous cloning to avoid borrow checker and lifetime complexity.

There's just one problem. Clones in Rust are expensive - far more expensive than in most mainstream languages. If you're not careful, your "high-level" Rust can actually run slower than garbage-collected languages like C#, TypeScript, or Python.

In this post I want to dig into why Rust clones are expensive, how they compare to other languages, and how to fix it so you can write functional Rust without tanking your performance.

Why Rust Clones Are Different

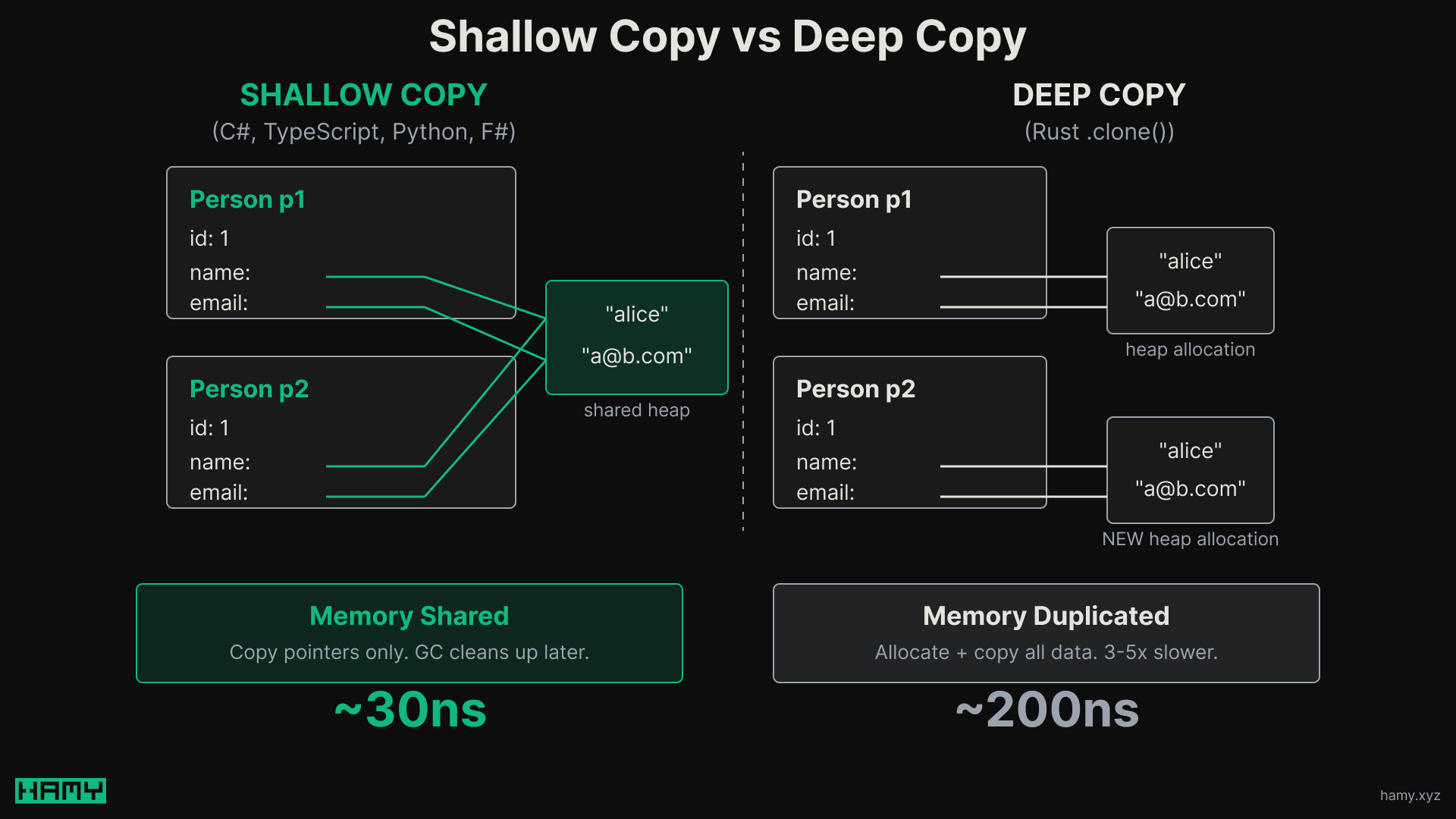

In most languages, "copying" an object is cheap because you're copying references, not data.

// C#

var p1 = new Person("alice", tags);

var p2 = p1 with { Name = "bob" };

// p2.Tags points to same memory as p1.Tags

// Only "bob" string is newly allocated

C#, TypeScript, and Python all do shallow copies by default - when you clone a record, you copy pointers to the existing data rather than duplicating it. The garbage collector handles cleanup later.

F# goes further with its default collections (list, Map, Set) which use structural sharing - when you "modify" an immutable collection, you create a new version that reuses most of the old structure. Only the changed nodes are new; everything else points to the same memory as before. This is similar to what the imbl crate does in Rust.

Rust does deep copies of structs by default. When you call .clone() on a struct with Strings and Vecs, you're allocating new heap buffers and copying all the data:

struct Person { id: i64, name: String, email: String }

let p1 = Person { id: 1, name: "alice".into(), email: "a@b.com".into() };

let p2 = p1.clone();

// id: bitwise copy (8 bytes on stack, essentially free)

// name: allocates new heap buffer, copies "alice"

// email: allocates new heap buffer, copies "a@b.com"

This is more technically correct - you get true independence between copies with no shared state. But it's also much slower.

How Much Slower?

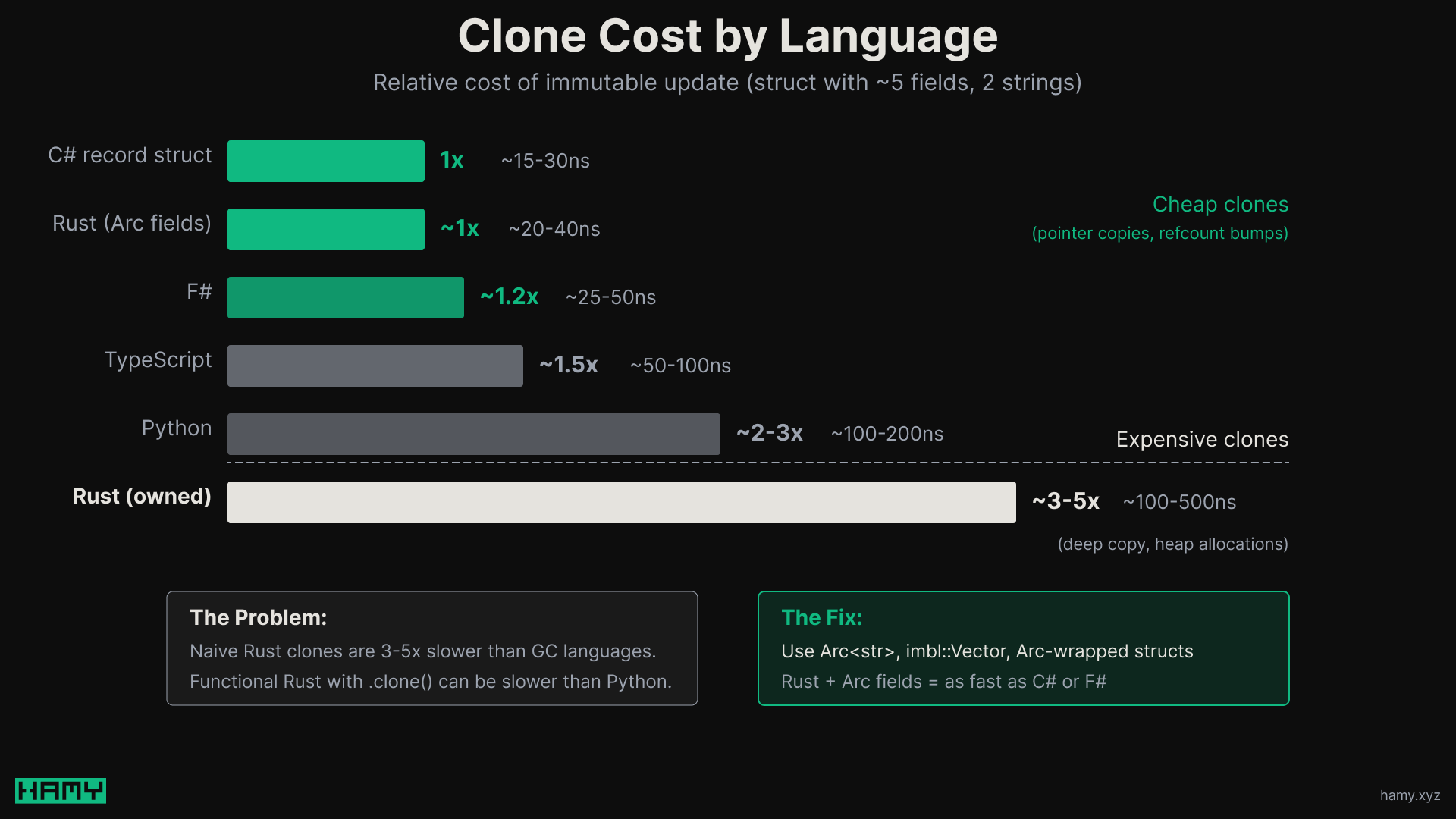

Here's an approximate performance comparison for a typical immutable update (a struct with ~5 fields, 2 strings):

| Language | What Happens | Est. Time |

|---|---|---|

| C# record struct | Stack memcpy, refs copied | ~15-30ns |

| Rust (Arc fields) | Refcount bump | ~20-40ns |

| F# | New heap object, refs copied | ~25-50ns |

| TypeScript | O(n) property copy, refs copied | ~50-100ns |

| Python | New dict/object, refs copied | ~100-200ns |

| Rust (owned Strings) | Deep clone all fields | ~100-500ns |

Naive Rust clones are 3-5x slower than the equivalent operation in garbage-collected languages.

The relative cost per immutable update shakes out to:

| Language | Relative Cost |

|---|---|

| C# record struct | 1x (baseline) |

| Rust (Arc fields) | ~1x |

| F# | ~1.2x |

| TypeScript | ~1.5x |

| Python | ~2-3x |

| Rust (owned Strings) | ~3-5x |

If you're doing functional transforms in a hot path - mapping over collections, building up state immutably, chaining operations - those 3-5x multipliers add up fast. You can easily end up with Rust code that's slower than Python for certain workloads.

Why GC Languages "Win" at Cloning

Garbage-collected languages get cheap copies by default because:

- Strings are immutable references under the hood

- They just copy pointers for unchanged fields

- The GC handles cleanup later

This is the tradeoff Rust makes for deterministic memory management. You pay the allocation / deallocation costs upfront instead of amortizing it through garbage collection. For mutation-heavy code, this is a win. For clone-heavy functional code, it's a tax.

How to Fix Slow Clones

There are two approaches:

Option 1: Don't Clone (Use Mutations)

The idiomatic Rust approach is to leverage the ownership system for safe mutations. This is what Rust was designed for - fast, safe mutations without garbage collection overhead.

If you have a hot path, reach for mutations. It's faster and more idiomatic.

Option 2: Make Clones Cheap

If you want functional pipelines with generous cloning (like I do with High Level Rust), you need to make your clones cheap. The way to do this is to make your Rust structs behave like GC language structs internally:

| Instead of | Use |

|---|---|

String |

Arc<str> |

Vec<T> |

Arc<[T]> or imbl::Vector<T> |

| Nested struct | Arc<ChildStruct> |

With Arc fields, clone becomes a refcount bump instead of a deep copy. Here's the difference in practice (benchmarks):

| Scenario | Standard Clone | Arc/Immutable | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10KB string | 83ns | 11ns | 7.5x |

| 10K element vector | 622ns | 41ns | 15x |

| 10K element hashmap | 2,200ns | 15ns | 147x |

| Nested struct (50 levels) | 1,900ns | 15ns | 127x |

Your clones become as cheap as C# or F#.

#[derive(Clone)]

struct Person {

id: i64, // Copy - no allocation

name: Arc<str>, // Clone = refcount bump

email: Arc<str>, // Clone = refcount bump

address: Arc<Address>, // Clone = refcount bump

tags: imbl::Vector<Arc<str>>, // Clone = pointer copy (structural sharing)

}

Helpful Crates

| Crate | What it does |

|---|---|

imbl |

Persistent collections (Vector, HashMap) with structural sharing - O(1) clones |

arcstr |

Ergonomic Arc<str> with literal support |

smol_str |

Small string optimization + Arc for larger |

bytes |

Bytes type, essentially Arc<[u8]> with slicing |

triomphe |

Faster Arc (no weak ref support) |

For collections, imbl is particularly useful. You trade slightly slower mutations for dramatically faster clones:

| Operation | Vec |

imbl::Vector |

|---|---|---|

| Clone entire collection | O(n) ~5-10μs | O(1) ~10-20ns |

| Random access | O(1) ~5ns | O(log n) ~30-80ns |

| Push/Append | O(1) ~10-30ns | O(log n) ~50-150ns |

If you're cloning more than ~50-100 times per mutation, immutable collections win on total time.

The Gotcha: Cheap and Expensive Clones Look the Same

The problem with the cloning approach is that expensive clones and cheap clones look identical in Rust:

expensive_struct.clone() // Deep copy, ~500ns

cheap_struct.clone() // Refcount bump, ~30ns

There's no type-level distinction. You can accidentally introduce an expensive clone and tank your performance without any compiler warning.

I'm working on LightClone to help with this - a trait that enforces cheap clones at compile time by ensuring all underlying data types are pre-determined to be cheap - Arc-wrapped, Copy, or known persistent data structures. It's early, but the goal is to make the type system catch expensive clones so you can avoid unexpected perf hits.

// This won't compile - String is expensive to clone

#[derive(LightClone)]

struct Person {

id: i64,

name: String, // ERROR: String doesn't implement LightClone

}

// This compiles - Arc<str> is cheap to clone

#[derive(LightClone)]

struct Person {

id: i64,

name: Arc<str>, // OK: Arc<str> implements LightClone

}

There are also some alias proposals in the Rust community to address this at the language level but they haven't moved much so unclear how soon they'll land.

Does This Actually Matter for Web APIs?

For typical web API backends: probably not much.

| Operation | Typical Time |

|---|---|

| Database query | 1-50ms |

| External API call | 10-200ms |

| JSON serialization | 10-100μs |

| Business logic (CPU) | 50-500μs |

| Clone overhead | 0.1-10μs |

Clone performance is noise compared to I/O latency. If 90% of your request time is waiting on the database, optimizing clone performance gets you... not much.

Where clone performance matters:

- Batch data processing

- Tight loops over large collections

- Game engines, real-time systems

- Anywhere you're CPU-bound

But for many of those you'll just reach for mutations anyway. So for general high level apps - reach for high level Rust, use LightClone to enforce cheap clones, and enjoy the devx improvements.

Next

Rust's clone behavior is one of the hidden costs of using it as a high-level language. Unlike GC languages where cloning is cheap by default, Rust requires you to think about memory and opt into cheap clones by using Arc and immutable collections.

The good news is once you know the pattern, it's not hard to apply. Use Arc<str> instead of String, imbl::Vector instead of Vec, wrap nested structs in Arc. Your clones become GC-language cheap while keeping Rust's other benefits.

If you're interested in this approach, check out LightClone - I'm building it to make the type system enforce cheap clones so you don't accidentally tank your performance. Star it on GitHub if you want to support it and continue to see it develop.

If you liked this post you might also like:

Want more like this?

The best way to support my work is to like / comment / share this post on your favorite socials.

Inbound Links

- Why I'm moving from C# to Rust for High-level Apps

- Benchmarking my Markdown Blog in Rust and C# - 4.6x Less Memory, 2-8x Faster Latency on the Same App

- What I Built in my First 6 Weeks at Recurse Center and What's Next (Early Return Statement)

- CloudSeed Rust - A Fullstack Rust Boilerplate for Building Webapps in Minutes

- 2026.01 Release Notes

- LightClone

- LightClone - Compile-Time Safety for Cheap Clones in Rust